I’m being a little bit cranky about my reading material lately. I want more from it—even while I don’t feel up to any emotionally scouring reads. Clearly, it’s possible for me to hold two contradictory desires at once!

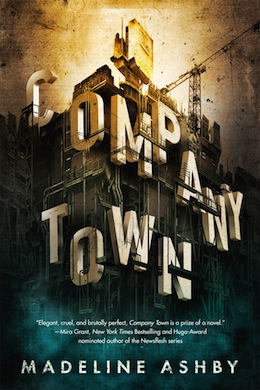

Madeline Ashby’s Company Town (Tor, 2016) is a very striking novel. Set on a city-sized oil rig in the Canadian Maritimes, in a future where almost everyone has some form of biotechnological enhancements—enhancements which operate under term-limited copyright licenses. Go Hwa-jeon is one of the few people she knows who is completely unenhanced. A school drop-out with a disorder that marks her skin and leaves her open to seizures, she makes her living as a bodyguard for the local sex workers’ collective.

At least until the Lynch family-owned corporation buys the rig and arrives in town. The youngest Lynch, Joel, is fifteen years old and the subject of numerous death threats. The aging family patriarch, Zachariah, believes these death-threats are coming from a post-Singularity future. Hwa isn’t convinced, but it’s a difficult job to turn down—especially when Joel is a nice kid, and there are plenty of non-timetraveling threats to his life in the meanwhile. And when her friends in the sex workers’ collective start dying—start being murdered—she needs the access working for the Lynch corporation gives her.

At least until the Lynch family-owned corporation buys the rig and arrives in town. The youngest Lynch, Joel, is fifteen years old and the subject of numerous death threats. The aging family patriarch, Zachariah, believes these death-threats are coming from a post-Singularity future. Hwa isn’t convinced, but it’s a difficult job to turn down—especially when Joel is a nice kid, and there are plenty of non-timetraveling threats to his life in the meanwhile. And when her friends in the sex workers’ collective start dying—start being murdered—she needs the access working for the Lynch corporation gives her.

Company Town‘s strengths are its sense of place—the oil rig community feels just as real and complex and screwed-up as any real-world small town going towards obsolescence and decay, with a gap between the haves and the have-nots large enough to put a boot through—and its characters. Hwa is a remarkably interesting protagonist, fully-rounded: hardened but not hard, occasionally vulnerable but never particularly trusting, with a sharp sense of humour. The characters that surround her are just as well-drawn. Ashby is also really good at writing violence—action—and its consequences. Hwa’s fights aren’t glossy, and she isn’t immune to the effects of violence and murder. It makes the novel hit vividly close to home.

Where Company Town falls down a bit, though, is the climax and conclusion. Events happen too fast or not fast enough, and seem a little bit jumpily disconnected: one or two are simply never explained, except with Singularity time paradox handwaving. I’m really grumpy about time-travel and time-paradoxes: they always feel like cheating to me.

On the other hand, Company Town is a really enjoyable read, and I’d spend more time in Hwa’s company any day of the week.

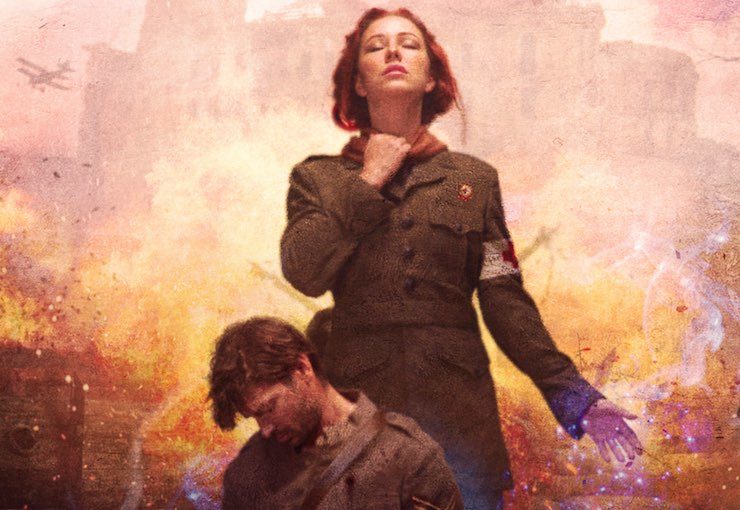

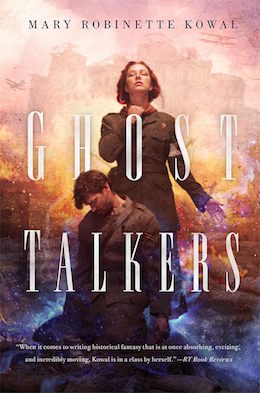

Mary Robinette Kowal’s Ghost Talkers (Tor, 2016) is a book I wanted to like and admire a lot more than I in fact did. Set during WWI, its major conceit is that the British are running a secret corps of mediums who glean information from recently deceased soldiers—whose spirits are conditioned to report in as soon as they’ve died—in order to better adjust to battlefield conditions. Its main character, Ginger Stuyvesant, is one of those mediums. An American heiress (with a British aristocrat for an aunt), her fiancé is an English intelligence officer, Ben. Ben’s starting to suspect that the Germans have caught on to the Brits’ ghost spies, and may end up targeting the British mediums. But it’s Ben, not Ginger, who ends up dead: when his spirit shows up in front of her, Ginger finds herself on a quest to track down his murderer, identify the German spies in the British command, and keep herself alive. This quest takes her into the mud and rot of the front lines, and into the middle of an infantry assault—among other things.

Mary Robinette Kowal’s Ghost Talkers (Tor, 2016) is a book I wanted to like and admire a lot more than I in fact did. Set during WWI, its major conceit is that the British are running a secret corps of mediums who glean information from recently deceased soldiers—whose spirits are conditioned to report in as soon as they’ve died—in order to better adjust to battlefield conditions. Its main character, Ginger Stuyvesant, is one of those mediums. An American heiress (with a British aristocrat for an aunt), her fiancé is an English intelligence officer, Ben. Ben’s starting to suspect that the Germans have caught on to the Brits’ ghost spies, and may end up targeting the British mediums. But it’s Ben, not Ginger, who ends up dead: when his spirit shows up in front of her, Ginger finds herself on a quest to track down his murderer, identify the German spies in the British command, and keep herself alive. This quest takes her into the mud and rot of the front lines, and into the middle of an infantry assault—among other things.

Ghost Talkers has an interesting concept. It’s very smoothly written—maybe a little too smoothly: the characters came across to me as oddly bland, and the final conclusion is a little bit too satisfactory and pat. Although Kowal does acknowledge the horrors of trench warfare—and the diversity of the people who fought in the battles of the Western Front—on an emotional level, it didn’t cut me deeply. For a book that had so close a connection to death, it views the war through the prism of Rupert Brooke, rather than Wilfred Owens: “some corner of a foreign field/That is for ever England,” and not “What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?”

For all that, it’s an entertaining read. I should like to see if Kowal does more in that setting.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books. She holds a Ph.D in Classics from Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.